Thomas K. Stephens was born into a Cornish mining family in July 1845. His father was a miner. Both his grandfathers were miners. It seemed his profession was preordained.

Despite earning a reputation as a skilled miner, the dangers of his vocation would grievously injure and maim him, and a harrowing accident would take his life.

In the beginning

When Thomas was just four years old, his family emigrated from southern England and settled in a growing mining community in Grant County, Wisconsin. As a young man, he left the area when the market for lead was no longer profitable.

Thomas spent over a decade north of the border. First, in Nova Scotia, he married Susan Elizabeth Day in January 1868 (16 months after the birth of their first child, Thomas Jr.) and proceeded to have five children (four of whom survived infancy). Next, the family made a brief stop in Newfoundland, where their sixth child, William John Stevens (my second great-grandfather), was born in March 1879.

By the following year, they had settled in Idaho Springs - a small mountain town that was the epicenter of Colorado's gold rush in 1859. Twenty years had passed since that first discovery of gold, but the town remained a powerful magnet luring miners eager to stake claims and strike it rich.

|

| Idaho Springs, Colorado - c.1882-1900 Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library Special Collections |

Thomas and his family's first recorded appearance in the area was the 1880 US census. They were enumerated living in his brother Richard's home. Curiously, Thomas was identified as "Maimed, Crippled, Bedridden, or otherwise disabled" in the census. Was there a mining accident in Canada that prompted the move to Colorado and convalescence in his brother's house?

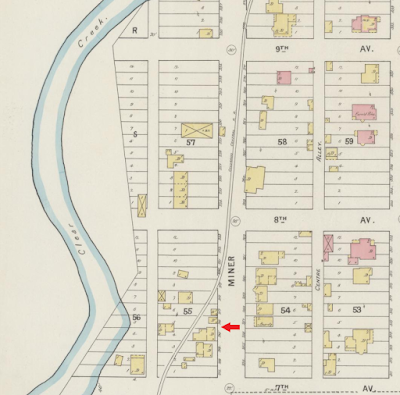

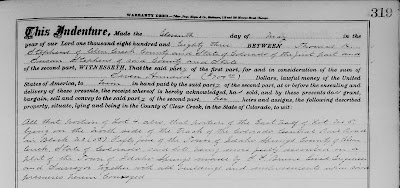

Within a couple years, Thomas had amassed enough funds to buy his own place. On July 1, 1882, Thomas paid $175 for two lots on Miner Street - the town's main thoroughfare, which are illustrated on the Sanborn fire map drawn up 13 years later.

|

| Excerpt of Thomas K. Stephens' July 1882 land indenture |

|

| Detail of 1895 Sanborn fire map for Idaho Springs The Stephens lots were #4 and the eastern half of #5 in Block 55 |

Legal battle builds principled reputation

Despite The Colorado Miner's assertion in 1878 that "mining is a paying industry and not gambling," it seems there was occasional volatility that hit miners like Stephens in the pocketbook. Two years after arriving in the Rocky Mountains, a legal dispute over unpaid wages helped identify Thomas' employer. On June 29, 1882, the Georgetown Courier wrote:

"This week several of the miners employed on the Hukill mine have quit work and placed their accounts in the hands of attorneys for collection. It seems the company is behind with the miners for the months of March, April, May and the portion of June past, not having paid them a cent of wages for that length of time. Upon inquiring into the facts of the case, we find that the company is in a bad state of financial embarrassment, and unless a large sum of ready money is forthcoming, the mine will be closed down."

On August 25, 1882, Thomas filed a lien against the Hukill Gold and Silver Mining Company of New York, which he alleged was indebted to him for $3,032.75 "for work and labor done by me and by the assignees of the claims hereinafter specified of which claims I am the assignor, under a contract with your agent..." The lien listed the wages owed to Thomas and 30 other miners, including his eldest son Thomas H. Stephens.

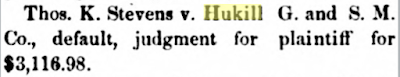

In December 1882, the court sided with Thomas and awarded him $3,116.98.

|

| Georgetown Courier - December 7, 1882 |

With a court order "in favor of Thomas K. Stephens and against the goods and chattels and real estate of the Hukill Gold and Silver Mining Company", the county sheriff advertised a sale of Hukill's property "at public vendue" to satisfy Thomas' claims. Thomas had prevailed on behalf of himself and his fellow miners and burnished his reputation as a man of integrity - committed to fulfilling the employment agreements he made with dozens of men.

|

| Plat diagram of the Hukill patent, recorded March 10, 1877 |

Mining just for fun

While Thomas was fighting for back payment from his previous employer, the Colorado Mining Gazette shed light on his workload and how he was making ends meet. In September 1882, they reported that the Star Tunnel site was being worked by day and night shifts and identified "Mr. T. K. Stevens (sic) is the contractor on this property."

|

| Colorado Mining Gazette - September 23, 1882 |

|

| Star Tunnel site (lower middle left) - c.1890-1910 Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library Special Collections |

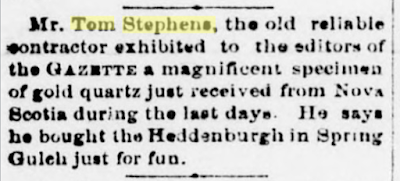

Later that year, another dispatch noted: "Mr. Tom Stephens, the old reliable contractor exhibited to the editors of the Gazette a magnificent specimen of gold quartz just received from Nova Scotia during the last days." Apparently, he had maintained links with his Canadian sojourn. The paper also disclosed Thomas' new hobby, announcing that "he bought the Heddenburgh [mine] in Spring Gulch just for fun."

|

| Colorado Mining Gazette - December 9, 1882 |

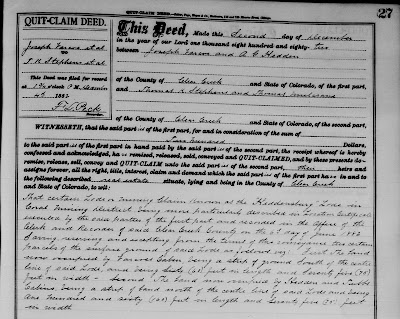

Sure enough, among Idaho Springs' land records is a deed dated December 2, 1882 documenting the $200 purchase of the mining claim known as the Heddensburg Lode in the Coral Mining district. Curiously, Thomas bought the lode with his step-father Thomas Mulcrane - the first indication that his mother, Sarah (Kitto) Stephens Mulcrane, was also in the area.

|

| Excerpt of Thomas K. Stephens and Thomas Mulcrane's 1882 purchase of the Heddensburg Lode |

Citizenship, Incorporation, and Wrasslin

In May 1883, Thomas sold to his wife Susan their lots in Idaho Springs. She paid him $700 ($525 more than Thomas paid for the property just ten months earlier). Why was he moving their real estate in her name?

|

| Excerpt of Thomas K. Stephens selling lots to his wife Susan |

The following month, Thomas' ancestral heritage was on display. A dispatch from Idaho Springs, published in The Rocky Mountain News, named the winners of the town's Cornish wrestling match. A second place prize of $40 in gold went to Thomas Stevens. It's unclear whether this is Thomas - who was 37 years old - or his son Thomas H. Stephens who was 16. Either way, it's a rare confirmation that a popular cultural activity from their homeland (known colloquially as "wrasslin" in Cornwall, where the form of wrestling originated) was still practiced.

|

| Rocky Mountain News - June 7, 1883 |

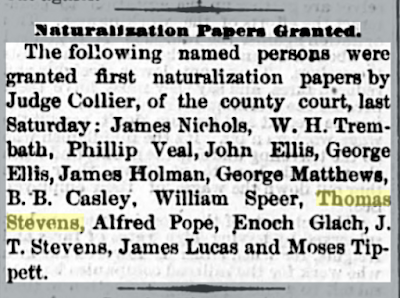

On July 6, 1883, an edition of the Weekly Register Call listed several men, including a Thomas Stevens, who "were granted first naturalization papers by Judge Collier..." Was Thomas working to become a U.S. citizen? These records aren't digitized and are archived in Clear Creek County's courthouse. I'll need to schedule a visit to learn more.

|

| Weekly Register Call - July 6, 1883 |

The very next day, Thomas began advertising his mining services. T. K. Stephens & Co. were in business as mining contractors offering "Practical Mining in all its Branches" and assured clients they would "Receive Prompt Attention and Thorough Execution." The ads ran through mid-1884.

|

| Colorado Mining Gazette - July 7, 1883 |

Operating his own business in a risky sector provides context and justification for why he likely applied for American citizenship and moved the family home - their largest asset - to his wife's name.

Injury amid financial hardship

In a series of peculiar transactions in July 1884, Susan Stephens appeared to be maneuvering her family's assets to pay mounting debts. On July 12th, she mortgaged her lots on Miner Street to Bella Ward for $100. Two days later, Susan used portions of this same property as collateral in a deal with Wilber Horn who paid her $1 (at 10% interest) to satisfy a $65.36 debt on a promissory note to Dennis Faivre, an Idaho Springs grocer (who routinely advertised himself as an agent who sold Sachs, Pruden & Co.'s famous ginger ale).

In September 1885, Thomas suffered his first noteworthy injury. While working as a fireman in the smelter for the Plutus mine (site of the former Hukill mine), Thomas "bruised his hand" and was left "laid up".

|

| Colorado Mining Gazette - September 19, 1885 |

|

| 1890 Sanborn Fire Map, detail of Plutus mine and smelter |

The extent of injury to Thomas' hand wasn't clear nor was its impact on his ability to work and earn a living. Despite an insurance policy, it appears Thomas' family continued to struggle with financial hardship.

A testy blurb in a February 1886 edition of the Colorado Mining Gazette (in which Thomas had advertised his mining services) aired his dirty laundry for their readership: "T. K. Stevens is the name of a gentleman who poked a Gazette at the postmaster marked 'refused'. Mr. Stevens should have done this before his subscription account ran up to $350 - which he still owes at this office."

|

| Colorado Mining Gazette - February 6, 1886 |

The following month brought some promising news. On March 1, 1886, Susan bought her lots on Miner Street back from Bella Ward. The Stephenses owned their home again.

Unfortunately, the danger of Thomas' work soon reemerged. During the summer, workmen at the Plutus mine were "digging trenches for the air pipe leading from the new compressor, run by water power," and huge blocks of granite were "being dressed down and laid for foundations" (Weekly Register-Call, September 17, 1886). On August 30, 1886, The Rocky Mountain News wrote of an "Accident at the Springs" that was detailed further by the Weekly Register Call:

"A deplorable accident occurred in the Plutus mine on Spanish Bar, above Idaho Springs, yesterday, to a miner named Thomas Stephens, where he had been employed for some time past, by the falling of a mass of rock weighing a couple of tons. Mr. Stevens was caught by the falling mass a little above the hips, inflicting serious injuries, which it is feared will result in death. Dr. Richmond was called from this city [Central City] to attend to the injured man, but entertains little hope for the suffering miner.

Tom Stevens (sic) has but one hand, the right one, but notwithstanding this, he is considered one of the best miners in the county, and was always in demand by mine owners when he was out of a job. Mr. Stevens is a real estate owner and a very worthy citizen, who has the deep sympathy of every one."

We learn for the first time that Thomas had lost his left hand - perhaps in the Plutus smelter accident nearly a year before - and was back in the mines when he was crushed by the rockfall. Despite initial speculation that his injuries would be fatal, Thomas made a rapid recovery during the fall of 1886 under the care of Dr. Richmond.

A strange fatality hovers

In June 1885, the Plutus Mining and Smelting Company of New York purchased the former Hukill mine after its assets were liquidated to pay debts owed to men like Thomas. Seven months later, in January 1886, the Plutus mine, mill, and smelter employed about 100 men and produced about $10,000 in ore each month (Rocky Mountain News, January 25, 1886). Under Plutus, profits for the mine increased $20,000 in its first six months of operation compared to the final six months under Hukill ownership (Rocky Mountain News, January 7, 1886).

|

| Mayflower, Plutus (highlighted), and Salisbury mines along left side and Hyland mine on right side across Clear Creek Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library Special Collections |

In October 1886, the Colorado Mining Gazette reported "Ninety-five thousand pounds of machinery arrived" for the Plutus mine. This investment included an air compressor that would "do an immense amount of hoisting, besides running fifteen three-inch air drills" (Colorado Mining Gazette, October 9, 1886). The foundations for the compressor were built during the summer, and it was during this work that Thomas was likely injured by falling rock.

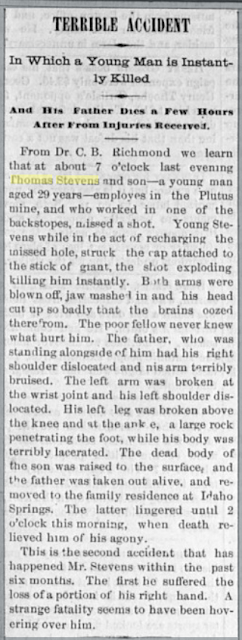

Despite the improvements to the mine's operations, it remained dangerous work. On Monday, November 22, 1886, Thomas and his eldest son Thomas H. Stephens were working inside the Plutus mine when disaster struck. Shortly after 6:00 pm, an "unlooked-for and dire accident" occurred and "two men full of life and hope were hurried into eternity; one instantly and the other a few hours later."

Before he succumbed to his wounds, Thomas K. Stephens recounted the chain of events that unfolded as he and his son were setting an explosives charge to blast rock inside the Plutus mine:

"He and his son had placed a portion of the charge of giant powder at the bottom of the hole and afterwards the fuse and cap, which was followed by more powder, which his son was in the act of pushing home with a tamper made by himself two days previously, of gas pipe with a stick in the tamping end, and thought by himself to be safe, when the explosion occurred" (Colorado Mining Gazette, November 27, 1886).

The coroner determined an inquest was unnecessary because he believed "that the men failed to push the cap and fuse home, and that when they were forcing the last part of the charge home the cap was struck by the tamping bar with sufficient force to explode it, and that if any mis-management or carelessness obtained at all, it was at that time" (Colorado Mining Gazette, November 27, 1886). Local papers ran with this assessment, writing that "T. K. Stevens made a statement a few minutes before his death, fully exonerating the Plutus management from all blame."

When the charge ignited prematurely, the resulting explosion killed the junior Stephens instantly "as he was terribly mutilated." He suffered gruesome wounds to his head, arms and torso. The senior Stephens, who was standing alongside his son, was thrown twenty feet from the stope to the bottom of the drift. He survived, was carried out of the mine and taken to his home on Miner Street where he lingered for nearly eight hours. He suffered a dislocated shoulder, broken leg, and lacerations to his body. The Rocky Mountain News wrote, "Everything was done by the medical attendants and others present to alleviate Mr. Stevens' anguished sufferings, which he bore without a murmur..." At 2:00 am, "death relieved him of his agony" (Weekly Register - Call, November 26, 1886).

The story was picked up by every newspaper in Colorado and many provided readers with graphic details of the injured.

The Weekly Register-Call observed, "This is the second accident that has happened [to] Mr. Stevens within the past six months. The first he suffered the loss of a portion of his right hand. A strange fatality seems to have been hovering over him." The Rocky Mountain News added that, in addition to being blown up by powder twice, Thomas had "also been twice crushed by falling dirt - the last time about three months since which laid him up till about two weeks ago, when he again resumed work in the Plutus."

|

| Weekly Register-Call, November 26, 1886 |

A decent interment for the dead miners

The death of Thomas and his son left Susan a widow at the age of 43 with four children to raise (her youngest was three years old and the oldest was 14). The Rocky Mountain News noted that his aged mother, Sarah (Kitto) Stephens Mulcrane, also resided in Idaho Springs.

|

| The Stephens family pictured in the early 20th century Susan Elizabeth (Day) Stephens is at center with her children |

The Colorado Mining Gazette praised Francis Osbiston, the wife of Plutus mine manager Colonel Frank Obiston, who jumped into action and was said to be "indefatigable in her attention to the bereaved family ministering with her own hands to their wants and personally overseeing and procuring the necessary requisites for the decent interment of the dead miners."

The community rallied around the Stephens family. "Several papers have been circulating this week for the benefit of the Stevens family" that resulted in significant fundraising. "Quite a large amount has been subscribed by our citizens for the benefit of the Stevens family" with Campbell & Mason (a local grocer) leading with a $25 donation. There was even talk of organizing an "entertainment for their benefit" that the Colorado Mining Gazette urged, "Let our local talent go to work upon this matter at once. If it is delayed, people will get cold." Mayor Elliott gained the support of the city's aldermen to donate a lot in the cemetery to the family.

The remains of Thomas and his son were prepared for burial by surgeon I. N. Smith who "has one of the tenderest of hearts, and his fingers are as dexterous and careful as those of the best surgeon in the land." His skills were essential considering the grisly injuries. "He was in constant attendance upon the unfortunate Stevens family, alleviating the sufferings of the father and tenderly smoothing the face and body of the poor battered and bruised son" (The Idaho Springs News, November 26, 1886).

During a funeral at the home, "Very appropriate and consoling remarks were made by the Rev. D. D. Van Antwerp of the Episcopal church." From the house, a "large concourse of friends and well wishers followed the remains to the cemetery, where the bodies of father and son were laid to rest side by side" (The Rocky Mountain News, November 25, 1886).

A stone obelisk marks the Stephenses' grave. Perhaps Francis Osbiston and the community had a hand in raising funds for the tombstone. The cemetery's logs record Susan Stevens as the purchaser for the family plot.

An inscription along the base of the stone says:

"Weep not for me oh my wife & children dear,

For I am not dead but sleeping here.

I was not yours but Christ's alone,

He loved me best and took me home."

|

| Memorial to Thomas K. Stephens and his son Thomas H. Stephens Idaho Springs Cemetery (photo by author) |

Epilogue

After the death of her husband and son, Susan raised her four children and never remarried. She died in Idaho Springs in January 1919 having outlived six of her eight children. Her death notice flagged that "It was the express wish of Mrs. Stevens that no flowers be sent for her funeral." She was buried in the family plot and her name was added to the stone obelisk.

The Plutus continued to operate although signs of difficulty emerged. A year after the Stephenses' death, a post in the Colorado Mining Gazette said, "There is no truth in the statements...that the Plutus mine had been sold." In June 1888, the Weekly Register Call reported that two men (W. R. Ireland and John Chavanne) were killed in an explosion in the mine. In January 1891, The Colorado Miner noted "that a miner working in the Plutus mine had his hand badly crushed."

By May 1891, the Plutus mine shut down as it was reportedly "consolidating into new hands in order that it may be developed to its full extent." The Georgetown Courier added that, "When the Plutus mine shut down it had 8 inches of 259 ounce ore in the lowest level. The difficulty seems to be, not with the mine, but that the management is not harmonious. A speedy adjustment of the matter is looked for."

In February 1892, The Rocky Mountain News reported, "The Plutus mine was sold to-day by Sheriff Josiah H. Bell, for the adjustment of the claim of the judgment creditor. The First National Bank was the purchaser, the price paid being $7,422.34." Days later, the Weekly Register-Call confirmed, "A Colorado Springs Mining company has purchased the Plutus mine on Spanish Bar above Idaho Springs. The price paid was $220,000." Reflecting on its glory days, it added, "The mine is well known and at one time was very productive under the management of Col. Frank Osbiston."

During the mid-20th century, interstate 70 was built through Idaho Springs, which changed the town's appearance and obscured obvious signs of the Plutus along Clear Creek. Today, the mining industry is gone. It's easy to overlook the history of the area's mining legacy, but it's there if you're willing to dig a little beneath the surface.

No comments:

Post a Comment